| Your guide to green living in Montgomery County, MD |

Picture this: an ancient adult stonefly lands on a stegosaurus. The stegosaurus doesn’t notice. The stonefly is looking for a mate, not a huge dinosaur, and it flies away. No big deal. The stegosaurus moves over to the river to get a drink. It swallows many gallons of water along with hundreds of ancient stonefly larvae. Again, nothing out of the ordinary. Jump ahead 165 million years to today. Adult stoneflies are still looking for mates. Larval stoneflies are still in streams and rivers. Today, no dinosaurs are around to bother them, but they are bothered by pollution and people-made changes. Stoneflies survived the dinosaurs. Will they survive people?

Stoneflies are not a fancy kind of house fly. They are in their own corner of the huge and diverse insect world. Currently about 3,500 species or kinds of stoneflies are found all over the world, except for Antarctica and some islands including Hawaii. The other 49 US states have stoneflies, including Alaska, which has stoneflies adapted to arctic conditions.

Stoneflies are not a fancy kind of house fly. They are in their own corner of the huge and diverse insect world. Currently about 3,500 species or kinds of stoneflies are found all over the world, except for Antarctica and some islands including Hawaii. The other 49 US states have stoneflies, including Alaska, which has stoneflies adapted to arctic conditions.

There are 10 species of giant stoneflies with 8 of them living throughout the contiguous US.¹ How gigantic are these insects? The adult giant stoneflies are about 2” long which may not sound big, but of all the 3,500 species of stoneflies, none are bigger.

They live for one to three years. All of their lives, except for a few days or weeks when they have molted for the last time and have wings, are spent underwater. They live in clean, clear, running streams and rivers that have high levels of dissolved oxygen.² In Montgomery County they are found in the Patuxent River watershed and the Little Bennett watershed. They live along the bottoms of streams and rivers, hiding under rocks and woody debris. To see a nymph, you have to move rocks and debris in the water and look closely. They have tiny claws on each of their six legs which helps them stay in one place despite the stream’s current.

They live for one to three years. All of their lives, except for a few days or weeks when they have molted for the last time and have wings, are spent underwater. They live in clean, clear, running streams and rivers that have high levels of dissolved oxygen.² In Montgomery County they are found in the Patuxent River watershed and the Little Bennett watershed. They live along the bottoms of streams and rivers, hiding under rocks and woody debris. To see a nymph, you have to move rocks and debris in the water and look closely. They have tiny claws on each of their six legs which helps them stay in one place despite the stream’s current.

Source: Troutnut.com

They are shredders, tearing apart leaves, sticks, and twigs. By the time giant stonefly nymphs find them, these materials are partly decomposed and are softer and easier to shred. In doing this they are breaking down dead plant materials and helping return nutrients and energy back to the ecosystem.

Frogs and fish are their primary predators. When they go through their final molt and become adults with wings, they are eaten by birds and spiders. They are easy prey because they are not very good flyers. That means they stay near the stream and in shady areas, sometimes under bridges. If you get to see a giant stonefly nymph or adult, consider yourself lucky!

Source: RenegadeFishers.com

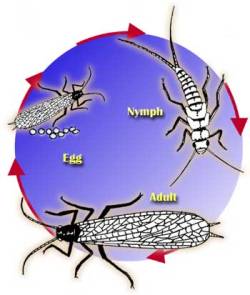

When it comes to life cycles, giant stoneflies are similar to dragonflies and our most recent visitors, the Brood X Cicadas. That is, they have incomplete metamorphosis. They do go from egg to adult with several stages or instars in between as they grow. But they don’t have the pupa (chrysalis or cocoon) stage that makes butterflies such stars in the insect world. There’s no complete change of appearance. The most noticeable difference between the nymph or immature giant stonefly and the adult giant stonefly is the wings that appear after their last molt.

This photo shows different sizes of giant stonefly nymphs. Source: FlyFishUSA.com

Giant stoneflies start as eggs. They’re covered with a sticky substance that keeps them attached to underground rocks or branches until they hatch and become nymphs. The eggs usually hatch after 2 – 3 weeks, live underwater, and are called nymphs, naiads, or larvae. The nymphs molt or shed their exoskeletons as they grow. The photo shows different sizes of giant stonefly nymphs. Before the last molt in the late spring or early summer, the individual stoneflies head for land and can be easily seen and caught by fish, frogs, or birds like herons and kingfishers. If a nymph makes it to land, it molts and gets its wings. Like we learned during our recent experience with Brood X Cicadas, the giant stonefly adults don’t have long to live after they mate and the female lays her eggs.

Giant stoneflies molt 12 – 36 times during the one to three years they’re alive. The different molts are called instars – 1st instar, 2nd instar, all the way up to 36th instar!

Giant stoneflies molt 12 – 36 times during the one to three years they’re alive. The different molts are called instars – 1st instar, 2nd instar, all the way up to 36th instar!Super Shredders! giant stonefly nymphs are joined by the larval forms of mayflies and caddisflies to make sure that less rotting plant material is left unshredded in streams. They’re to decaying plants what vultures are to dead animals. YUM!

Super Sensitives! They are among the critters called macroinvertebrates (macro meaning you can see them without needing a magnifying glass, invertebrates meaning they don’t have a spine or any bones). Figuring out what macroinvertebrates live in a particular stream helps us know the overall quality of that stream. If a stream has giant stonefly nymphs, it’s got plenty of dissolved oxygen and not many pollutants.

Super Survivors! They’ve been on earth long past the dinosaurs. What more proof do you need of this superpower?

A big pat on the head – watch out for their antennae! – for our giant stoneflies! We wish we had more streams that meet your high standards!

Giant stoneflies aren’t on either the Maryland or US list of threatened and endangered species, however they are a rare occurrence.

Giant stoneflies are important indicators of high quality streams. They won’t live in every stream in Montgomery County because a lot of our streams wouldn’t meet their dissolved oxygen needs. However, we want to preserve those areas in our county that can meet their needs. They contribute to their ecosystems as shredders of decaying plant materials in streams.

We also know that where there are giant stonefly populations, there may also be trout living nearby because they have the same requirements for good water quality, dissolved oxygen, and cool water. Where there are trout, there are people trying to catch trout and that’s an important benefit to those people in our community.

We also know that where there are giant stonefly populations, there may also be trout living nearby because they have the same requirements for good water quality, dissolved oxygen, and cool water. Where there are trout, there are people trying to catch trout and that’s an important benefit to those people in our community.

In environmental education programs students of ALL ages (PreK to 12th grades, college, graduate students, and life-long learners), can learn how to do stream water quality assessments based on what macroinvertebrates (worms, snails, clams, insects, and crustaceans) they find living in the streams they test. To further people’s interest in what lives in our streams and what that means for water quality, the Audubon Naturalist Society (ANS) in Kensington has created a free user-friendly phone app called CREEK CRITTERS®. You can even get involved in a community science project that uses the app (information below).

We can’t answer the question raised earlier: Will the giant stoneflies survive people? But we can make sure that we do what we can to keep them alive and well. Here are some ideas.

Guest writer: Gail Melson

Don’t miss out on next week’s blog highlighting the stream critter: The Marbled Salamander!

______________

Citations:

¹Contiguous US means the states that share borders with each other; sometimes called “the Lower 48.”

²The amount of oxygen available to living aquatic organisms.

³https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plecoptera

Please tell me where to sign up for a password.

Patricia, thank you for the message. The blogs are all available without a password. If by any chance you come about one that needs a password, it is because staff are in the process of reviewing and approving it before it is published to the public without a password. I confess, I’m still learning and this is the way I have figured out to have our staff review blogs while working remotely. Other than that everything on MyGreenMontgomery is available without a password. Let me know if there were other questions.